Type One energy has announced its intention to use a retired TVA coal plant site, the Bull Run Fossil Plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as the site for a prototype fusion reactor with the hope to eventually commercialize fusion power – and maybe even find a neat way to use old EV batteries to help power the process.

The Bull Run Fossil Plant was a coal-powered generation facility first opened in 1967 and shut down on December 1, 2023 – just over two months ago. It was run by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the largest public utility in the US, and sits just across the river from Oak Ridge, the site of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), one of America’s most important national science labs.

Despite only being shut down for two months, claims are already being made on the site. Due to its close location to ORNL, a lab that has studied fusion since the 1950s, it seems a natural choice for another fusion experiment – enter Type One energy, a company looking to work toward the commercialization of fusion power.

Type One Energy ambitiously gets its name from Type I on the Kardashev scale, a theoretical measurement intended to describe how advanced a civilization is. A Type I civilization is able to harness all of the energy available on a single planet – currently, humanity’s total energy production is about three orders of magnitude, or a thousand times, below this benchmark.

So, just starting with the name, Type One’s goals seem… optimistic, to say the least.

What is fusion?

For a basic primer on what we’re talking about here, Nuclear Fusion differs significantly from Nuclear Fission. Fusion is the reaction that happens inside of stars like our Sun, whereas Fission is what powers current commercial nuclear reactors.

Fission, in current nuclear reactors, takes large, rare, radioactive atoms (like Uranium-235) and splits them apart, which releases energy when the bonds between neutrons in the nucleus of these atoms are broken. The major downside is that this reaction creates radioactive material, with nuclear waste still being an unsolved problem.

Fusion, however, works by taking smaller atoms and fusing them together. The most promising fusion reaction uses deuterium and tritium, two rare isotopes of hydrogen that have extra neutrons in their nuclei. Deuterium is rare, but still relatively easily found in normal seawater (about one in every 6,000 natural hydrogen atoms are deuterium), whereas tritium is almost nonexistent in nature and would be manufactured by splitting lithium atoms.

Incidentally, this is a potential use for lithium from old EV batteries.

When the deuterium and tritium atoms are fused together it creates a normal helium atom and releases a free neutron, from which energy can be harvested.

The upside of fusion is that it does not produce radioactive waste, and that it is incredibly energetic, with the amount of deuterium in 1 gallon of ordinary seawater (about half a milliliter of deuterium) theoretically able to generate the amount of energy from combusting 300 gallons of oil. Fusion reactors are also considered to be inherently safer as there is no possibility of a meltdown.

The downside is that fusion requires extremely difficult conditions to occur, and those conditions cost a lot of energy to maintain. You can get a hint of this by looking at the location where fusion naturally happens – at the center of stars, at temperatures of tens of millions of degrees and pressures of trillions of pounds per square inch.

The state of fusion today

So it sounds like a science fiction concept, and ever since it was first envisioned in the 1950s, it has been. Humanity has never been able to achieve a fusion reaction that generated more energy than it took to create… until recently.

You may have heard the news last year that scientists had achieved “net energy gain” from a fusion reaction. This means that more energy was released by the fusion reaction than the amount of energy from the lasers used to produce the temperatures needed. This is denoted by the symbol Q, with Q numbers above 1 meaning net energy gain. The current record is Q = 1.54.

But that’s not everything, because not all of that energy can be effectively harnessed, so in order to reach the point where fusion actually becomes viable for electricity generation, the reaction must create enough energy to become self-sustaining – as long as more deuterium/tritium fuel is added, the reaction will continue, much like adding more logs to an already-burning fireplace.

The primary technology advancement needed for the Type One facility is high-temperature superconducting magnets, which have generally seen remarkable progress in recent years and are now the focus of multiple companies working to adapt the basic technology for fusion energy applications. Given what is known from a scientific development standpoint, ORNL considers the step envisioned by Type One as reasonable and achievable. While success is not guaranteed, we view the risk-to-reward profile of this facility as appropriate. If successful, the results from this facility would provide a solid basis for a second-generation facility focused on energy production.

Mickey Wade, associate lab director of fusion and fission energy and science, ORNL

For a self-sustaining reaction, a ratio of about Q = 5 is thought to be necessary to reach the level of viability for electricity production. But once that milestone is reached, Q increases arbitrarily, because the self-sustaining nature of the reaction means that little to no energy will be needed to be spent externally to maintain the reaction.

Type One’s plans

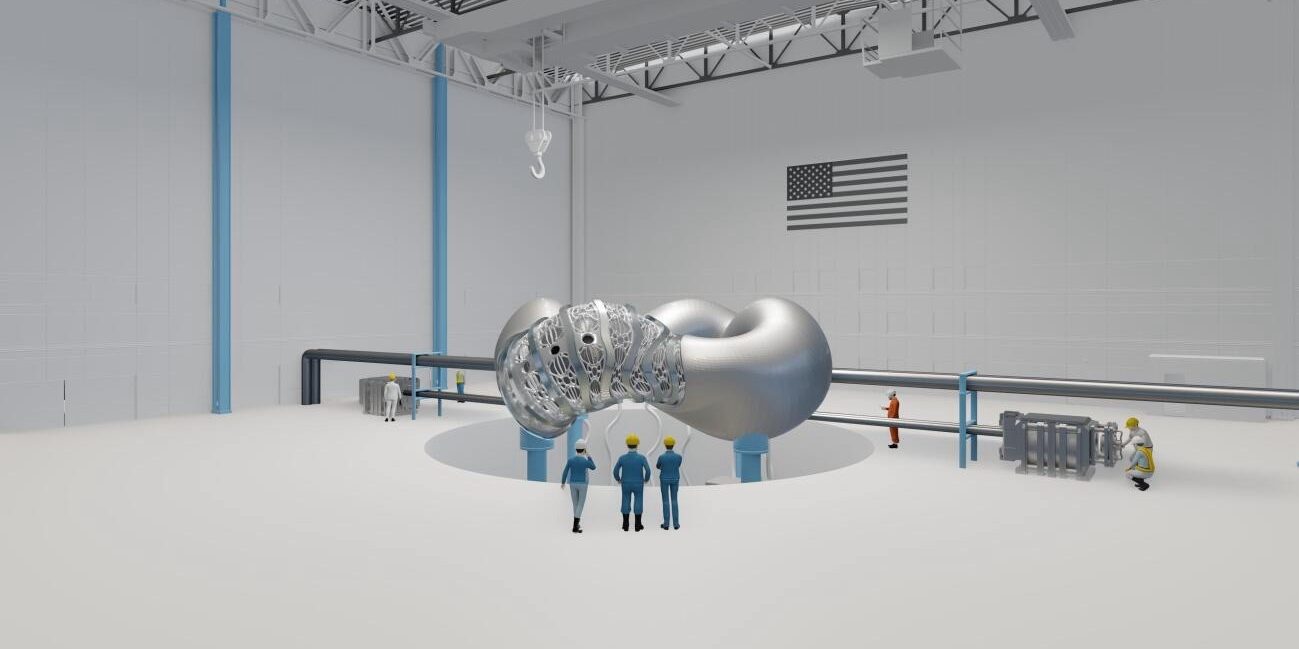

Type One thinks it can reach this milestone, though probably not for years still – it sets the target at about a decade from now. As of now, it wants to build a prototype reactor it’s calling Infinity One at the Bull Run site, with the intent of “retiring risks” before building a future pilot power plant.

There are a number of other fusion reactors in the world, but most of them are from public institutions run by academic, governmental, or intergovernmental sources. There are a few other fusion startups, but Type One thinks that it will be the first private company to build a functional stellerator prototype. Fusion reactors come in two types: stellerators and tokamaks, with each having their advantages but tokamaks being more common.

Many of the company’s personnel have already been part of stellerator projects in other settings, so there is plenty of expertise associated – including CTO Dr. Thomas Sunn Pederson, who we spoke to for this story, who previously worked on the record-setting W7X stellerator in Germany.

The plan has been enough to get the company noticed by some government entities, with the Department of Energy choosing it as one of eight companies to receive part of $46 million in funding. Here’s the full list of those companies, six of which ORNL is also partnering with:

- Commonwealth Fusion Systems (Cambridge, MA)

- Focused Energy Inc. (Austin, TX)

- Princeton Stellarators Inc. (Branchburg, NJ)

- Realta Fusion Inc. (Madison, WI)

- Tokamak Energy Inc. (Bruceton Mills, WV)

- Type One Energy Group (Madison, WI)

- Xcimer Energy Inc. (Redwood City, CA)

- Zap Energy Inc. (Everett, WA)

Type One is also the first company to receive grants via a new Tennessee program to encourage innovation and investment in nuclear energy, and closed an investment seed round of $29 million last year.

As for involvement from TVA and ORNL, both entities are “collaborating” with Type One, but are a little more measured in their expectations than the company itself is.

TVA is a clean energy leader. With the retirement of Bull Run plant, TVA is in the unique position to partner with Type One and ORNL to explore the repurposing of a portion of the facility toward the advancement of fusion energy research. As TVA works to be net-zero by 2050, we must work together to identify potential clean energy technologies of the future. Being able to further the advancement of fusion energy research provides a win-win proposition for TVA and the people of the valley.

-TVA spokesperson

Despite Type One’s announcement today of its selection to pursue the use of TVA’s Bull Run site, TVA issues a reminder that the project is contingent on proper completion of necessary environmental reviews, permits, operating licenses and so on. While TVA has signed a memorandum of understanding with the company and with ORNL, it hasn’t yet formally agreed to lease part of the property to Type One. But it does see the unique opportunity to use a former coal for research into the future of energy, especially in a spot that’s so close to one of the centers of American fusion research at Oak Ridge labs.

Construction on the pilot research project could start as early as 2025, and be completed as early as 2028.

Electrek’s Take

This story interested me primarily due to the angle of turning a site that used to generate the dirtiest possible electricity into one that generates what would likely become the cleanest form of electricity, which is quite poetic.

And fusion energy, in particular, has incredible promise if it’s ever achieved. It could solve a tremendous amount of our societal problems – but like everything else, this only works if the benefits are properly distributed, and our current sociopolitical systems aren’t all that great at doing that.

But it could, at least, help to solve climate change, by offering a highly energetic energy source that also releases zero emissions, and has even fewer auxiliary impacts than other current clean energy sources (e.g. habitat disruption, panel/turbine recycling, and so on). And, relevant to Electrek, if lithium is needed to make tritium, then that gives us something we could use recycled EV batteries for, which is pretty cool.

But we also shouldn’t get too far ahead of ourselves here, because it sounds like this project is in very early stages. Today’s press release is a pretty minor step – Type One is just announcing the site that it wants to use, which hasn’t even been secured yet. And while we had a great conversation with Type One, the responses we got from TVA and ORNL were much more noncommittal. So there was an excitement disconnect there, which is to be expected between a company and a government entity, but it still reminded us that all of this is still some ways off.

So there’s a lot of steps between here and fusion energy, and frankly, I think that the biggest breakthroughs in fusion are not likely to come from a private company but from academic or governmental research, at least for the time being.

We will eventually need companies to come in and figure out commercial viability, so getting started on that earlier than later is all well and good, but we’re still going to be waiting for a while before that viability happens – and unfortunately, we don’t have time to wait to solve climate change. So, while fusion might help, we still need to get to work now on emissions reductions immediately.